The Poet Who Saved One Heart

Loss, kindness, and the quiet legacies we never see

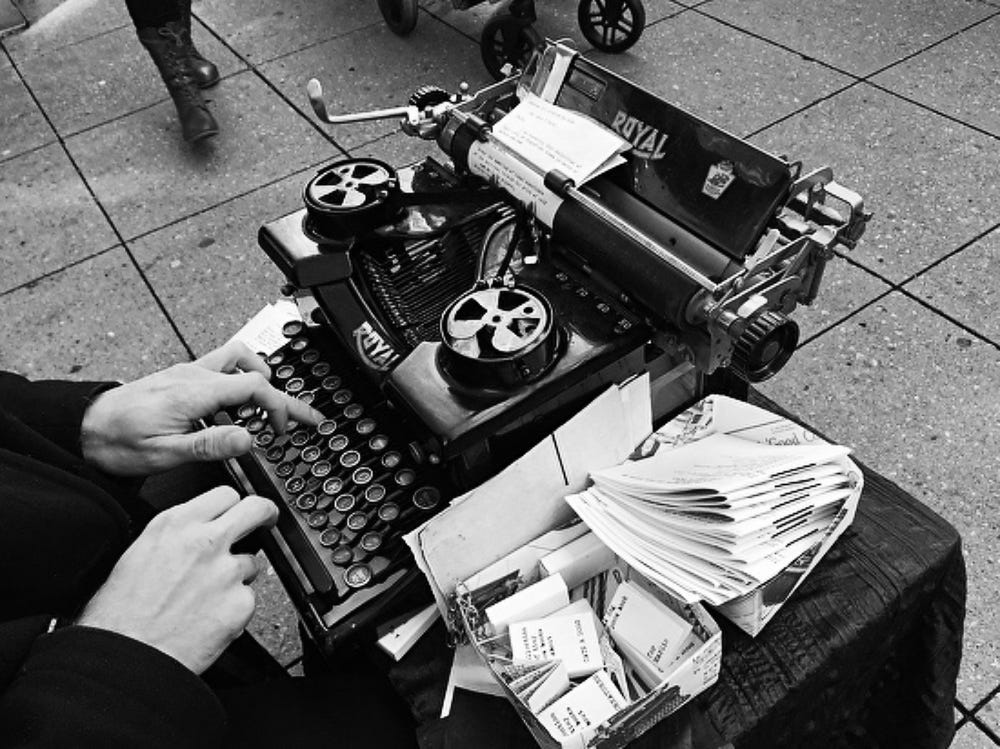

He always parked his dilapidated Mazda many blocks away, beyond the downtown meters, to save what little money he had.

His equipment was heavy, and he had to lug it all the way back to the business district. The weight and strain aggravated his lower back, already weak from aging and a bulging disc he could not afford to repair.

Some of the equipment rested on a small cart with wheels that he carefully navigated over potholes, debris, and sidewalks. The rest, stuffed inside two large backpacks, he carried as the straps bit deep into his shoulders.

Passing motorists and pedestrians sometimes shouted profanities at him. Others crossed the street to avoid him. They thought he was one of those homeless or mentally ill who wandered the city, busking or begging.

He endured this ritual every Christmas season because once he made it downtown and set up his holiday poetry stand, people saw him differently.

He’d wear a Santa hat with a scarf, arrange little sheets of onion paper and envelopes, and begin plinking away on an old typewriter. He looked like a character from Charles Dickens, and soon shoppers and pedestrians inquired about his poems.

“So, you’re a poet,” one distinguished, older gentleman in a suit and overcoat said to him, while juggling a few shopping bags.

“Correct,” he said to the man.

“And I see from your sign that you’ll type out a poem, for a donation of whatever amount I choose.”

“Yes, sir. Leave me your name, and whatever topic you’d like me to include, and I’ll compose a poem for you. I’ll need about twenty minutes, as several folks are already in the queue. When you return, I’ll have your poem in one of these envelopes, with your name written on it. You can read the poem, and if you like it, perhaps leave a donation,” he said with a smile.

The man gazed at the poet’s old typewriter and said, “That sure is an old typewriter. I can’t imagine you making a living doing this?”

The poet looked up and said:

“If I can stop one heart from breaking,

I shall not live in vain;

If I can ease one life the aching,

Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting Robin

Unto his nest again,

I shall not live in vain.”

“Hey, that’s pretty good,” the old man said to the poet.

“Not mine. Emily Dickinson,” the poet said.

The old man smiled and said, “Okay, I’ll shop and come back. I’m an attorney, but my passion is landscape painting. So maybe write me a poem about painting? My name’s Joel Swanson.”

“My pleasure, Mr. Swanson. I’ll see you when you come back,” the poet said.

And so it went like this.

Shoppers strolled by, and their intrigue led to questions. They’d return to collect their poems and most were delighted and left generous donations.

Mr. Swanson came back with even more shopping bags and said, “Howdy, I can’t wait to see what you’ve written for me.”

“Ah yes, Mr. Swanson, here you go,” and the poet handed him the envelope containing his poem. Mr. Swanson set down his shopping bags, opened the envelope, and carefully slipped out the delicate onion skin paper.

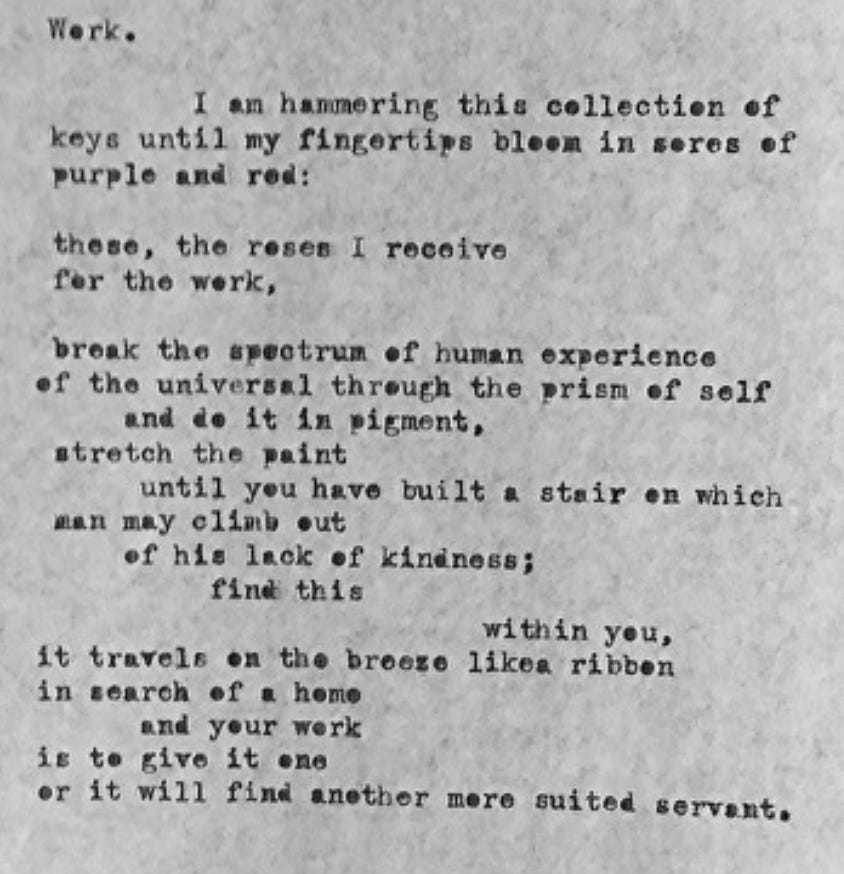

He read the poem aloud:

“Work.

I am hammering this collection of keys until my fingertips bloom in sores of purple and red:

these, the roses I receive

for the work,

break the spectrum of human experience of the universal through the prism of self

and do it in pigment,

stretch the paint

until you have built a stair on which man may climb out

of his lack of kindness;

find this

within you,

it travels on the breeze like ribbon in search of a home

and your work

is to give it one

or it will find another more suited servant.”

Mr. Swanson stared at the poem and his eyes misted. He dug into his wallet and handed the poet two twenty-dollar bills.

“Thank you, I needed this,” the old gentleman said as he slipped the poem back into the envelope, gathered his shopping bags, and then disappeared into the crowd.

The poet returned each day, with all his gear, and vigorously typed away for his holiday customers.

And each late afternoon, as the sun descended behind mountain trees and streams of soft light cast shadows across the buildings, he’d pack his gear and labor up backstreets to his tucked-away car.

He lived in an aging condominium complex, in a two-bedroom corner unit upstairs that housed his books, a rescue cat named Brodsky, and a closet full of his late wife’s clothing and things.

He tried once to donate everything, but then put it all back.

She may be lost to me now, he’d think, but the clothing and remnants make me feel less lonely. Like a part of her remains with me, until the very end.

Since he was a little boy, books were his life and he longed to become a writer.

Literature helped him escape a dysfunctional family life, where his alcoholic father often released the demons within him on his wife and son. Sometimes he escaped to a little tree house in the woods, where he kept a collection of books inside an old Tupperware container. He’d bring a flashlight and sit on a blanket in the corner of the tree house, reading and listening to the hooting owl in a nearby tree.

After high school he worked at the local carwash and attended community college, eventually earning an associate degree in English. He wanted to transfer to the University, but there was no money after his father skipped town. He found an entry-level job at the post office and used the income to support himself and his mother.

All the while, he kept writing.

He’d sent some manuscript proposals to various literary agents over the years, but they were all rejected. “Too literary, too poetic. Even for upmarket fiction,” one agent wrote back.

So he started a blog, commented in various online literary forums, and published short stories in writer and poet magazines. Over time, he developed a loyal following. With the advent of social media, he grew his following even more.

It was through Facebook that he met his future wife.

She had reached out to him and said she admired the humanity of his poems. They’d message one another, and he learned that she lived in the same town, where she taught third graders.

They arranged to meet in the cafe section of a local bookstore and thus began a love affair and eventual marriage that lasted twelve years. Until her diagnosis, rapid decline, and death two years ago.

Her death sent him into a deep depression.

He stopped writing for months, and his concerned readers sent comments and emails online. He’d always been a shy and private man, and he had few friends. He realized that his community of online followers was a kind of loose family, and their concern about his welfare moved him.

But the depression persisted until two things happened.

The first occurred in the early morning hours after a winter cold front brought a dusting of snow. The soft mewing sound came from the stairs outside his condo, and when he opened the door, a small kitten shivered and looked up at him.

“Where did you come from?” he said, picking up the kitten gently. He fed the kitten, and the next day visited the veterinarian’s office. “He’s more or less healthy, just a bit underweight,” the vet said, adding, “And he has no chip, so he’s probably feral.”

Back home, the poet told the kitten, “You know, I was reading some poems by Joseph Brodsky the night before you showed up. Brodsky was a cat lover, so why don’t we call you Brodsky?”

The kitten was indifferent, like all cats.

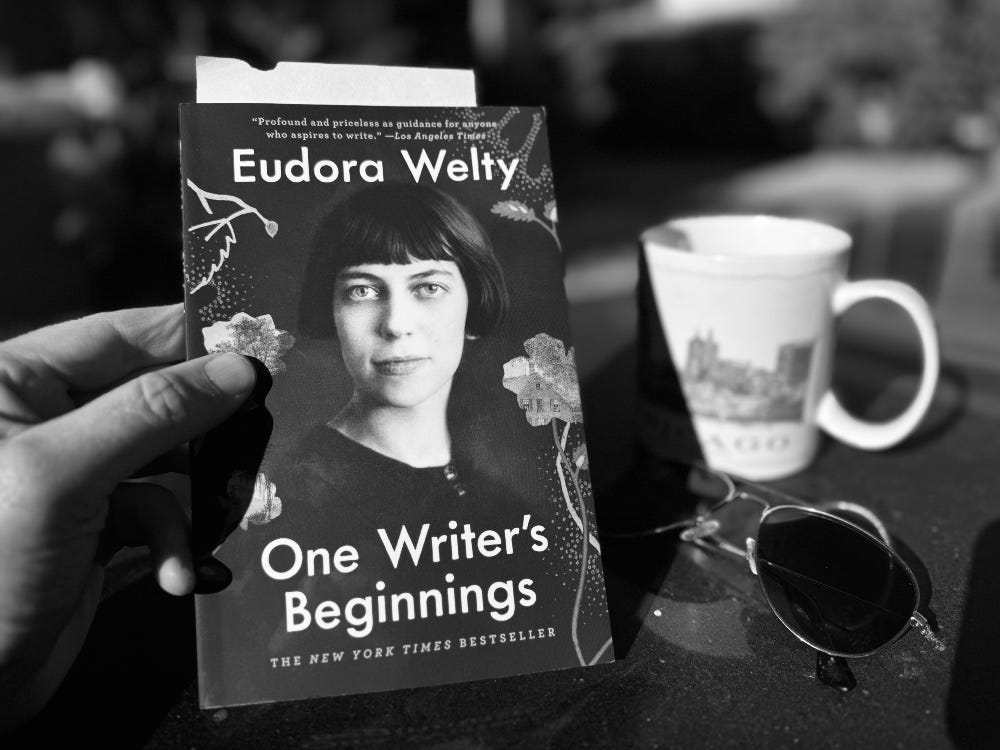

The second thing that lifted the poet out of his depression was a thin little book titled, “One Writer’s Beginnings,” by the late author Eudora Welty. It was in the spring, and he’d read the following line in the book:

“All experience is an enrichment rather than an impoverishment.”

He’d realized that the years together with his wife were a tremendous blessing. She helped him become a better writer and a better person.

But the experience of losing her, he finally comprehended, was not an impoverishment. Difficult and devastating, yes. But it had enriched him with feelings of deep gratitude.

How lucky he was to have had her in his life.

Her death taught him volumes about loss, that universal thing we all face sooner or later. This deeper appreciation for love and loss influenced the depth of his writing, which he finally returned to with a renewed sense of purpose and inspiration.

Much to the thrill of his online following, the poet began posting again and submitting short stories and poems to literary publications.

He was promoted at the post office, where stray postcard musings and the menagerie of people he met informed his writing. He often thought of the late poet and writer Charles Bukowski, who worked for ten years in a post office.

He sometimes recited the following Bukowski poem:

“there are worse things

than being alone

but it often takes

decades to realize this

and most often when you do

it’s too late

and there’s nothing worse

than too late”

Years passed and the poet’s beard grew gray, and Brodsky moved slower due to arthritis in his hips. Despite all his efforts, the poet never found an agent or publisher, and he accepted the fact that his work would not reach the kind of audience big-name writers achieve.

He stayed positive, reminding himself that writing was a joy, regardless of fame or fortune. But sometimes, he couldn’t help but wonder. Did I choose the right path? What if I’d followed a different passion?

These doubts began to plague him until the day he received the letter.

Most of the poet’s readers communicated with him via email, but occasionally he received a good old-fashioned letter in his post office box.

It was a Saturday when he slipped into the UPS store to check his mail, and there he found a cream-colored envelope with his name and address neatly typed on it. It was not often that he received a letter composed on a typewriter.

“Old school purist,” he thought with a smile.

There was a return address typed on the top left corner of the envelope, bearing the name S. L. Foster.

He opened the letter and read the following:

“I have been following your poems and stories for three years, and you are my favorite writer. There is such deep humanity and compassion in your work. Especially the things you have written about loss. I lost my parents two years ago. A terrible car accident. And being an only child, I understand loss. Like you, I channel it into my writing. My goal is to become a novelist. Anyway, I just wanted to thank you for inspiring me and so many other writers.

With respect and admiration,

S. L. Foster”

The poet’s eyes began to well with tears.

He opened his laptop and did a search for S. L. Foster. He found a website and discovered Sally Laura Foster’s exquisite writing. She looked to be in her mid-twenties, but her writing was beyond her years in depth, cadence, and wisdom.

The poet wept upon reading one of Sally’s blog posts about the death of her parents. How terrible, he thought, that this bright young woman was denied the love and support of her parents.

He noticed a button at the bottom of Sally’s website that read, “I need your support.” He clicked it and landed on a GoFundMe page.

Sally, he was impressed to discover, had applied for and been accepted into the Columbia School of Art’s rigorous MFA writing program. But Sally had a problem.

Tuition, fees, and living expenses to complete Columbia’s two-year MFA program would easily exceed $100K, and she didn’t have the money. Yes, she could apply for school loans, but it would take years to pay them off. Not to mention, it’s difficult for even talented writers to make a good living.

The poet sat in front of his old Corona typewriter and began typing a letter to Sally.

“Dear Miss Foster,

Thank you for your thoughtful letter. I was deeply moved by your kind words. I took the liberty of visiting your website, and I’m not surprised that Columbia accepted you into their writing program. You are truly gifted.

I want to help.

I possess little money, but I have a decent following of devoted readers. If you’ll allow me, I’d like to share your story with them, including the link to your GoFundMe page.

Every little bit helps!”

He sent the letter and by the end of the week, Sally wrote back, thanking him for the offer and graciously accepting any help.

With that, the poet took to his laptop and wrote a newsletter post about Sally, the tragedy of her parent’s death, and her dream of attending Columbia’s MFA program.

He included the following in his post:

“I have always admired dreamers. The artistic souls who choose the path less traveled, because that is where dreams are found. Sally dreams of Columbia, and perhaps with your help, we can launch one of tomorrow’s great novelists.

Remember what Oscar Wilde wrote: ‘Yes: I am a dreamer. For a dreamer is one who can only find his way by moonlight, and his punishment is that he sees the dawn before the rest of the world.’

Won’t you join me in helping Sally?”

The poet looked over at Brodsky, who lay in the sun on the edge of the window sill.

“You were an orphan too, Brodsky. What do you say we help this young woman?”

And with that, the poet hit send on his laptop.

In the following month, donations poured into Sally’s GoFundMe page.

She emailed the poet and thanked him for all his help, and he replied to ask how much she received. “Nearly twenty thousand dollars,” she wrote back. “That’s amazing,” he replied.

What he didn’t convey was his sense of disappointment. Not with his readers, whose generosity in helping Sally moved him deeply. Rather, he was sad because he knew the donations would likely taper off.

And there were not enough funds to make Sally’s dreams of Columbia become a reality.

A few more weeks passed and donations to Sally’s GoFundMe page slowed to a trickle. The poet thought about sending out a final plea but realized he couldn’t do that to his loyal readers.

They’d already given what they could.

The poet was never a big believer in fate, but that changed one morning as he sipped his coffee. Brodsky was purring on his lap, and the poet had just read the following Ralph Waldo Emerson quote:

“Once you make a decision, the universe conspires to make it happen.”

The poet set down his Emerson book and picked up his iPad to check email messages from his website. The name on one of the emails was distantly familiar.

He read the email out loud:

“My dear poet,

Not sure you’ll remember me, but you were kind enough one Christmas season downtown to craft a little poem for me about painting. I want you to know that your poem changed my life.

I was a stressed-out attorney. Never took vacations. Drank too much. My wife was ready to leave me. I was a jerk to people. The only peace I ever found was when I took a few hours on the weekends to paint.

I put that lovely poem you wrote for me into a frame.

My favorite line was about stretching the paint ‘until you have built a stair on which man may climb out of his lack of kindness.’ Every day before I went to the office I read your poem.

And then, one day, I picked up the frame and sat on the edge of my bed, re-reading the stanzas of your poem. Something surrendered inside me.

And I knew what I had to do.

By the end of the day, when I told my wife I was selling my law firm, she broke down in tears of joy. I told her I wanted to paint, travel, and become a kinder man.

The law practice sold for millions. I paint every day now. We travel. And I have you, my dear poet, to thank for that.

By the way, I read your newsletter about the young writer, Sally. I made a hefty donation. I remembered the Emily Dickinson poem you quoted to me years ago. That bit about ‘If I can stop one heart from breaking / I shall not live in vain.’

Anyway, Sally should be all set for Columbia. I wanted you to know because whether you realize it or not, your writing has changed people’s lives for the better.

Let me know if you ever need anything.

-Joel Swanson”

“Good Lord,” the poet said, nearly spilling his coffee as he set down the iPad. He looked over at the cat. “Brodsky, we did it! Sally is going to Columbia!”

Many miles away, sitting in her apartment, Sally Laura Foster spilled her teacup upon checking her GoFundMe page. A man she never heard of donated the maximum amount allowed on GoFundMe, a staggering 100K.

Attached to the donation was the following message:

“A wise poet once quoted Emily Dickinson to me: ‘If I can stop one heart from breaking / I shall not live in vain.’ Enjoy Columbia, Sally. I look forward to reading your future novels.”

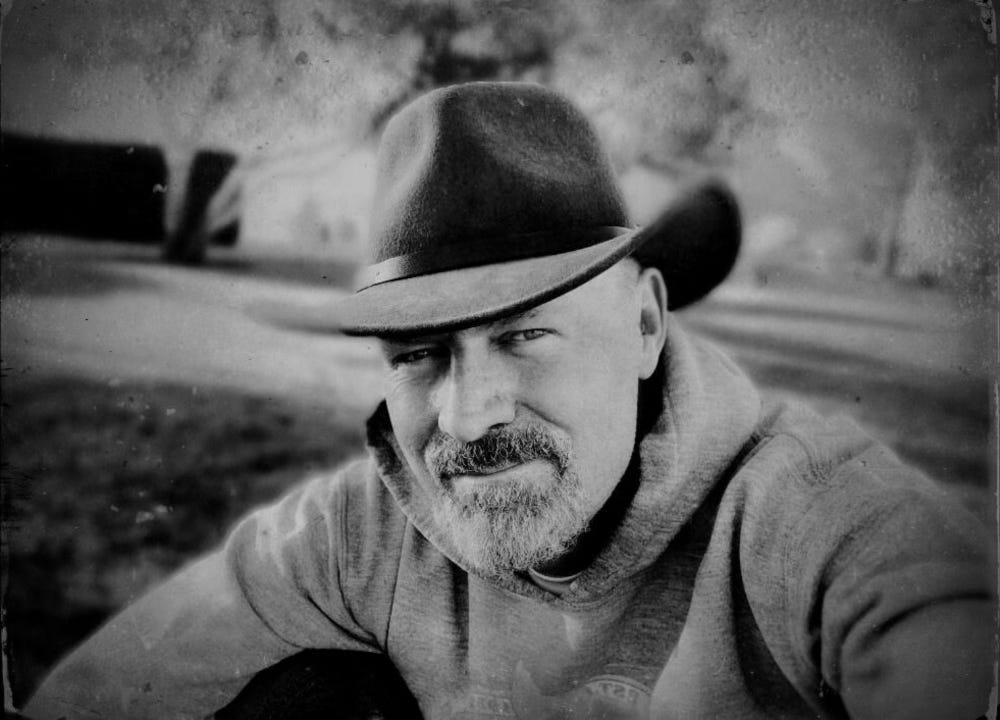

Time passed and the poet was now an old man.

His beloved cat Brodsky passed on, but the poet was at peace with life and contented himself in the company of books. Like his boyhood days reading in the treehouse, the poet now sat in a large leather chair in his condo, immersed in literature.

He’d long since retired from the post office, and he closed down his website a year ago. He still published occasional stories in various publications, but mostly he found joy in reading.

Near the holidays, he drove downtown to enjoy a coffee and browse the bookstore. He was too old to sit on the sidewalk typing poems for holiday shoppers, although a few locals still recognized him warmly.

As he approached the bookstore, he spied all the new arrivals in the display window.

Under a sign that read “Pulitzer Prize Winner in Literature” was a book titled, “I Shall Not Live in Vain.” The illustration on the book’s cover was an ink bottle with a feather quill. And there, at the bottom of the book’s cover, was the author’s name.

S. L. Foster.

The bells attached to the entrance door rattled as the old poet hurriedly walked inside. He grabbed a copy of Sally’s book, took it to the register, and quickly paid for it. Then he ordered a latte from the bookstore’s coffee shop.

He found a chair, took off his hat, sat down, and placed Sally’s book on the table.

He opened the book, and the first few pages were full of raving comments and blurbs from notable novelists and literary reviewers. On the third page, the old poet found the following dedication:

“For the poet who inspired me, and for JS. My eternal gratitude.”

He thought of the Richard Dreyfuss movie, “Mr. Holland’s Opus.”

In the film, Dreyfuss plays an aspiring composer who takes a temporary job teaching music at a high school. But the temporary position becomes a decades-long career. Dreyfuss’s character discovers that the great symphony he thought he’d write was not his true calling. His true calling was to be an educator. He found he loved his students and his work deeply.

Sometimes the thing we become is greater than what we long to be.

The old poet sipped his latte and thumbed through the pages of Sally’s book. He thought of his late wife. He remembered Brodsky’s soft purrs in the morning. He called up memories of his days writing poems for holiday shoppers like Joel Swanson.

Behind him, near the back of the bookstore, was the classics section. He looked over his shoulder, glancing at the various titles. Somewhere near the top of the shelves were various works by Emily Dickinson.

“If I can stop one heart from breaking, I shall not live in vain,” he said to himself.

And then he put on his hat, clutched Sally’s new book, and headed for the door. He wanted to get home.

He had more stories and poems to write.

More breaking hearts to save.

Before you go

This journal continues because a few readers quietly support it. If these pages matter to you, a small one-time gift below helps keep the work going.

Thank you for reading.

Subscribe to Weiss Journal.