The Hog's Breath Inn

Memory and sanctuary in Carmel-by-the-Sea

Carmel-by-the-Sea was where we went to mend ourselves.

It was where the abrasions of ordinary life were softened by sand and sun and salt air. We went there to feel whole again, if only for a day or a weekend.

My father would fire up his Lincoln Continental, a car that otherwise slept quietly in the garage and emerged only for occasions that mattered. Relatives in town. A trip to the coast. My mother and I would climb in with our sweaters and books and suntan lotion, and I would bring my sketchbook, already imagining the day ahead.

The drive over Highway 17 was always an ordeal.

Curves. Hills. My father’s impatient, jerky driving. I held my breath through much of it. But once we turned off Highway 1 onto Ocean Avenue, my mother and I would exhale together, as if the town itself had taken us in and said we were safe now.

My father would find a parking spot near the Mediterranean delicatessen, where he bought lunch meats, cheeses, rolls, and sodas.

We would stop at the bakery for cookies. Then we would ease back into the Lincoln and roll down Ocean Avenue toward the beach parking area, unhurried and ready to enjoy our lunch.

From the trunk my father would pull his old green army blanket.

We carried everything across the warm sand and down the slope until we found a place that felt right, usually near one of the windswept cypress trees. The soothing breeze moved through the brush and branches.

We ate our sandwiches and cookies and drank our sodas. California chipmunks appeared, their striped backs flickering through the bushes. They crept closer, fearless and hopeful. I would hold a small piece of food in my hand and wait until one of them gathered the courage to take it.

Then we read. We let the sun work on us.

The surf moved in and out. The breeze cooled us. Full bellies and warm light conspired to pull us toward sleep. Even my father’s snoring could not prevent it. We lay there on the army blanket, motionless, probably looking like a trio of exhausted drunks.

We were not alone. Carmel had that effect on people.

Eventually we stirred. My father lost himself in one of his war novels. My mother walked the shoreline, studying the grand homes along the coast. I sketched the chipmunks and stole glances at the bikinis passing by, thirteen years old and keenly aware that something in me had begun to wake up.

The afternoon spent itself easily.

Then the sun dipped and the air cooled. We packed up, brushed off the sand, and climbed back into the car. My father drove us up the hill and toward dinner at the Hog’s Breath Inn, a favorite spot owned by Clint Eastwood.

I was a devoted Eastwood fan and always hoped we might see him there, pouring drinks behind the outside bar as people claimed he sometimes did.

But we never saw him there.

Inside, we studied the menu and tore into the warm French bread. My parents talked. I studied the paintings on the walls and the people around us. Across the table sat two young couples, early twenties maybe. The women were radiant, long-haired and tan and impossibly assured. I stared longer than I realized until my father interrupted.

“Don’t worry, Johnny,” he said with a small, knowing smile. “Your time will come.”

I felt embarrassed and strangely buoyed all at once. We ordered dinner. I kept scanning the room, still half-expecting Eastwood to appear. After dessert my father paid the bill and we stood to leave. I must have looked a little deflated. My mother placed her hand on my shoulder.

“Don’t worry, Johnny,” she said. “Someday you’ll bump into ol’ Clint.”

We never did, not during all those years in Carmel.

My father was right about the other thing, though. Time did come. There was a lovely girl in high school, and then others, and eventually a career in law enforcement and a marriage and a life that moved steadily forward, carrying me farther from those afternoons on the beach.

Years later I returned to the area for a two-week law enforcement management course. I was newly promoted, still learning how authority sat on my shoulders. One evening a few of us went out for drinks. I suggested the Hog’s Breath Inn, half joking about finally meeting Clint Eastwood. One of the others laughed and said Eastwood owned the Mission Ranch now. A beautiful place, he said.

So we went there instead.

In the piano bar I mentioned that I used to sing and play in a band in college.

One of my classmates pushed the idea that I should play something. The pianist said customers were not allowed to touch the piano anymore. Apparently someone had ruined that privilege long ago.

My friend mentioned that we were all police lieutenants in town for a class. He showed his shield. He bought the pianist a drink. I protested weakly.

Eventually the pianist spoke to a man in a three-piece suit. The man looked over at me. I waved, a ridiculous little gesture. The pianist returned and asked if I was any good.

“I’m decent,” I said.

“One song,” he said.

I slid onto the bench, nerves buzzing. The bar was full. People gathered close. I began playing Billy Joel’s “Piano Man.” Somehow my voice held. People sang along. Even the pianist surrendered the bench. For a few minutes the room belonged to me.

When I finished and stepped away, applause followed. The pianist leaned toward me and spoke softly.

“Clint enjoyed it,” he said. “He’s over there.”

In a dim corner Clint Eastwood sat with two men, a glass of red wine in his hand. I was surprised we hadn’t seen him earlier. I approached, heart pounding.

“Mr. Eastwood, thank you for letting me play your piano,” I said. “I’m John.”

He stood, shook my hand, and smiled.

“Nice job,” he said. “I hear you’re all policemen.”

We talked briefly. He wished us well. It was polite. It was surreal. After all those years, I had finally met him.

And for reasons I could not yet name, it left me feeling oddly hollow.

Later that evening I drove through Carmel alone. On impulse I turned up San Carlos Street and parked beneath a familiar lantern and sign.

Hog’s Breath Inn.

I walked the narrow path to the outdoor bar, past the dining room, past the table where we once sat together, my parents and me, full of food and longing and promise.

I took a seat at the bar and ordered a Diet Coke.

I thought of my parents. Of the beach. Of the blanket. Of my father’s steady reassurance. Of my mother’s quiet faith.

Meeting Clint Eastwood had been something, but it was not the thing.

The best things in life are not the idols we chase or the names we finally touch. They are the people who know us completely and love us anyway. The ones who shape us without asking for credit. Even when they are gone, they remain. Their voices. Their hands on our shoulders. Their confidence in us.

I finished my drink, looked around one last time, and walked back to the car.

The long way home felt right.

Before you go

This journal continues because a few readers quietly support it. If these pages matter to you, a small one-time gift below helps keep the work going.

Thank you for reading.

Subscribe to Weiss Journal.

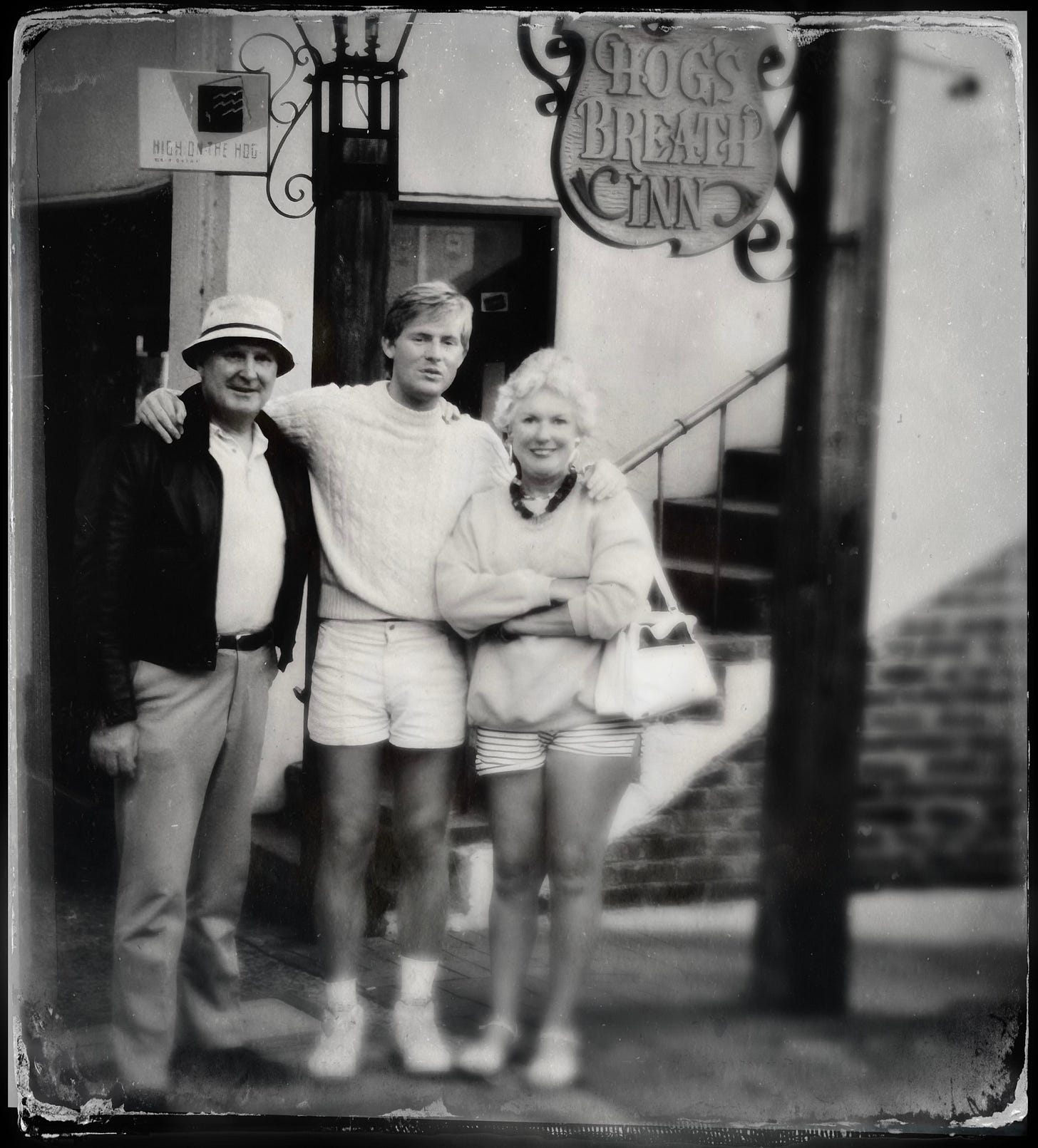

Love this so much! It seems like you just leaned back, closed your eyes, and the memories rolled out, the writing effortless. What great parents you had. You look like Robert Redford in ‘The Way We Were’ in the photo with your parents. 😁

Beautiful memories shared, thank you. Growing up in Southern California, my parents had a road trip planned nearly every summer; and I enjoyed them fully, following the map with my finger. Your story reminded me of my own father’s army blanket, which was thin (but very warm) and carried the many scents of the elements. Among the flares, flashlight, and assorted tools, the blanket was a staple in the trunk of dad’s car. As a young girl, I remember complaining about the smell, itchiness, and offending color, unthinking of the memories that it might have carried for my dad. Today I wonder if it offered comfort during his days as a lonely soldier (his words) during the Korean War. When he tossed it away-he smiled to me and said “adios, itchy blanket.” Back then, I thought, “good riddance!” Now, I wish that I would have asked more questions to learn what accompanied stories were left along with it.