Everyone Can Agree on a Kitten

Small mercies, quiet souls, and the unexpected grace that saves us

“My older brother once pulled the chair out as our mother was about to sit,” he said softly, before I poured his coffee.

“That’s terrible. Why did he do that?” I said.

He didn’t answer.

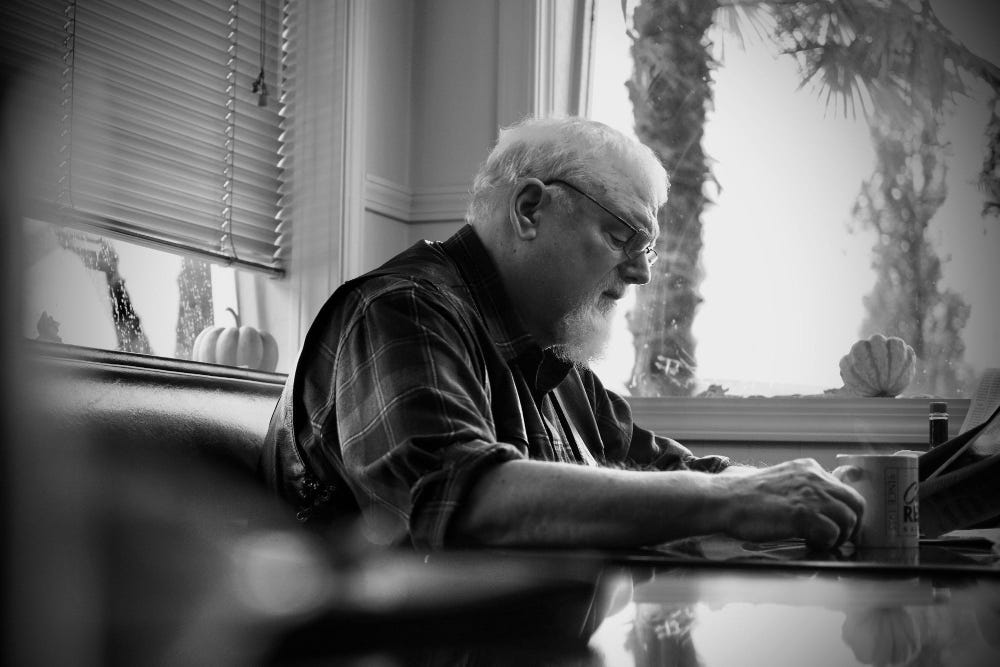

He stared at his newspaper and coffee mug. Then he gazed out the window where palm trees swayed in the breeze. There was something peaceful in the movement of the trees. Free and unencumbered. Their gentle back and forth reminded me of the metronome on my piano teacher’s baby grand, the pendulum swaying like a hypnotist’s watch. It used to mesmerize me when I was a boy.

This was different.

The rocking palms hadn’t entranced the old man. Deeper things held him. Remnants of the past. Ghosts, or maybe regrets.

I looked at the menu beside his newspaper and then back at him.

“Would you like to order anything from the kitchen?”

“Have you got any mulligans?”

“Excuse me?”

“Do you play golf, son?”

“Uh, no sir.”

“Mulligans are second chances. Opportunities to take another shot. Have another go.”

“Yeah, we don’t have any of those in the kitchen. But Ned makes terrific buttermilk pancakes.”

“Haven’t you ever wanted another opportunity? A do-over?” His voice held a melancholy timbre.

“Well, I’d like a second chance with Mary Sue, but she dumped me last year for some fraternity dude. If I could repeat high school, I’d pay more attention, get better grades. That way I’d be in college now, instead of waiting tables.”

“If you don’t have any mulligans, guess I’ll try Ned’s pancakes.”

He handed me the menu and looked back out the window at the palm trees and ocean waves in the distance.

I gave Ned the order just as Katie skipped in from the back door.

“Did you feed the kitten?” she asked.

“No, I’ve been busy working.”

“You and Ned are worthless,” she said, pulling a small bowl off the shelf to pour half and half into. She went into the little storage room in back, where she kept the kitten.

She found the poor thing shaking under a box in an alley and tried to convince her friends to adopt, but no one stepped up. I thought about it, but my allergies are terrible, and I’m not home enough. It wouldn’t be fair to the kitten.

Katie put on her apron and I took my break.

Ned fixed up some breakfast for me. I was about to pour myself a coffee when the old man eyed me and said, “Would you mind topping off mine?” I stepped over and said, “Here you go. I’m gonna take a break to eat, so if you need anything, Katie over there is your gal.”

“Join me,” he said, to my surprise.

Normally I don’t sit down with customers. I like to eat by myself, so I don’t have to make conversation. But the old guy seemed sad and lonely. I fetched my plate and coffee and sat down across from him.

“You mentioned college earlier, and something about bad grades,” he said.

“Yeah, I was never a great student. I can’t sit still. Guess I’m better with my hands than with book stuff.” I took a few bites of food as the old fellow gazed out the window for a second.

“My brother was like you. Good with his hands. He could fix anything. Had a little auto repair shop for years before the cancer got him.”

“I’m sorry. Do you have any other family?”

“Nope. Lost my parents a lifetime ago, and then my brother last year. My wife Betty died six years ago. Just me now, a tattered coat upon a stick.”

“Hey, wait, I know that line. My Dad used to say it. It’s from some Irish poet?”

“That’s right. W. B. Yeats. ‘An aged man is but a paltry thing, A tattered coat upon a stick.’ The poem is ‘Sailing to Byzantium.’ It’s about immortality, art, the human spirit.”

“All that stuff is over my head,” I said as I took more bites and eyed the clock on the wall. Ned only gives us thirty-minute breaks. The old man noticed me looking at the clock.

“Time is all we have, and then it gets late in the day, and the sun hangs low.”

“But there’s always tomorrow.” I was trying to be upbeat.

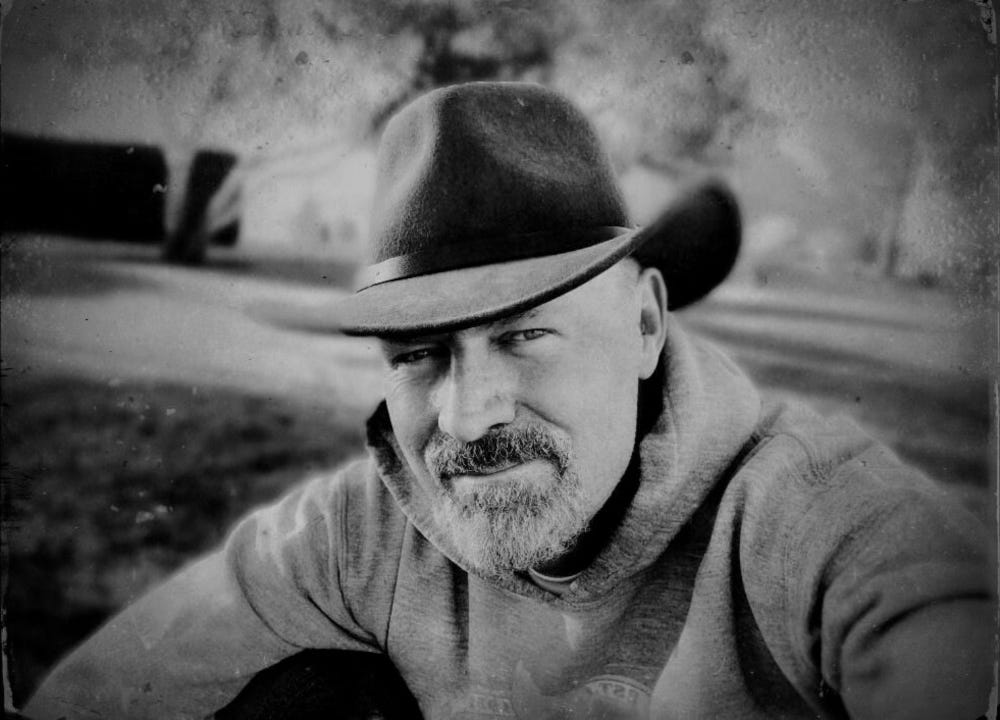

“I used to love the sun. I used to wonder why old people were always pale. Get some color, I used to think. But then I found out. With age comes skin cancer. Actinic keratosis. Spots. So you avoid the sun. Wear hats and long sleeves. Forever pale, like a ghost.”

He sipped his coffee.

“My Dad used to say ‘Don’t get old,’ but what’s the alternative? Dying young?” I chuckled after saying it, trying my best to be conversational.

“I used to run and lift weights. I liked being fit. But then I got a hiatal hernia and had a knee replacement. That killed the workouts. I turned to my love of fine wine, but the hiatal hernia gave me GERD. I lived on antacids but finally gave up wine. GERD forced me to raise the top half of my bed, so I don’t inhale acid when I sleep. But the raised bed aggravates my lower back. Your father is right, don’t get old.”

“What about swimming? It’s a great low-impact workout,” I suggested.

“Tried it. But I’ve got a slow thyroid. Makes me very sensitive to cold and temperature change.”

I was running out of things to say, but then he continued.

“The other day I dropped my iPad and when I picked it up I must have activated the reverse camera feature. An old man stared back at me, and I barely recognized myself. There was a time when my hair was dark and I had a chiseled jawline. But it all goes. So you grow a beard to hide the double chin. You find looser shirts to hide the weight. You try. For a while, you try.”

“You look pretty squared away to me. Distinguished and all,” I said.

He looked out at the ocean and said, “I heard the old, old, men say ‘all that’s beautiful drifts away, like the waters.”

“That’s poetic,” I said.

“Not my words. Yeats.”

There was an awkward silence. I wondered why he invited me to sit with him. I tried to enjoy my meal but the old man’s despair hovered in the same way that sorrow can taint a conversation.

“Well, aren’t you two a sad pair,” Katie said as she poured more coffee into our mugs.

There is a light in Katie that’s hard to explain. Sure, she has youth and beauty, but somehow I think she’ll forever shine. Her exuberance is infectious. Goodness in people is like a magic elixir, teasing light out of the darkest souls.

She smiled at the old man and said, “I overheard you. I have to say, Yeats knew how to turn a phrase, but he was dead wrong.”

“Is that so, miss?” The old man raised his eyebrows and leaned back, like a professor ready to pounce on an impetuous student.

“Absolutely. That line about ‘all that’s beautiful drifts away, like the waters,’ is just a bunch of defeated, old man poppycock.”

“Poppycock? Well, wait until you’re old and no longer a lovely young thing. Wait until your body rebels and people die and…” but before he could finish she interrupted him.

“Nonsense. Beauty doesn’t die. It might drift away, like receding water, but it comes back in new ways. Youth to wrinkles, age to wisdom. There’s always hope and beauty, you just have to open your eyes.” Katie smiled and seemed pleased with herself.

But the old man wasn’t convinced. He’d been wearing his pity and despair for some time. “No offense, young lady, but you sound like a Hallmark card or one of those treacly self-help gurus.”

“Doesn’t change the fact I’m right. Beauty is everywhere. We can enjoy it even when we’re old. In fact, it might be sweeter when we’re old.”

“Prove it, young lady.”

“Fine, I will,” Katie said as she set down the coffee pot and left us.

“She’s got spunk,” the old gentleman said.

“Oh, you have no idea. Katie is getting her degree in psychology. She works here weekends. She’s a force of nature. The customers adore her.”

Katie returned with a cardboard box, which she plopped down in the middle of the table. She reached inside and pulled the kitten out.

“I named her Mary, after the late psychologist Mary Ainsworth.” Katie placed the kitten on the old man’s lap.

“Mary Ainsworth? That’s an odd name for a cat,” I said.

“Well, Mary pioneered a technique known as the ‘strange situation,’ assessment. Like dropping a kitten on someone’s lap,” Katie said.

The old man sat there, holding the kitten on his lap. He began to stroke her fur. Something seemed to shift in him.

“What you are holding right there, good sir, is beauty. It doesn’t matter if you’re young or old. Because everyone can agree on a kitten. And I’ve put all her food and toys in the box, so you’re all set.”

“All set? Oh, no, I can’t possibly take her,” the old man said.

“It’s you or the animal shelter, and they have more cats than they know what to do with. Who knows what will happen to little Mary? I’ve already asked my friends, but we’re all busy with university life. It’s up to you,” Katie said.

Ned called out with an order up, and Katie darted back to the kitchen.

“She’s a beautiful little kitten,” I said.

“Oh, don’t you start,” the old man said.

But he kept petting her.

We didn’t see the old man and his new kitten for nearly a week, but he finally came back into the diner and slid into the booth by the window.

“How are you and Mary getting along?” I asked.

“Mary is a terrible name for a kitten. I renamed her ‘Luna,’ because she lights up my evenings. Before Luna, the nights were the worst.”

He pulled out his mobile phone and showed me the screensaver photo of Luna sitting on a couch, surrounded by cat toys. Then he sat back and looked out the window, at the palm trees and ocean.

He was quiet for a moment.

“You know, last week when I was here, I was thinking about giving up. About finishing my breakfast and going down to the beach. Wading out into the surf, and letting it take me.”

I was speechless. He kept staring out the window, then he turned and faced me.

“You asked me last week why my brother pulled the chair out from under my mother. Truth was, he was angry with her. He’d found a stray dog and wanted desperately to keep it, but Mom said no. We had to give the dog away. And my brother, well, he had emotional issues. He was never quite right.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“Yeah, there was always something missing with my brother. A kind of sadness. I always thought that if Mom had just let him keep the dog, maybe he would have turned out differently. Better.”

“Animals brighten our lives,” I said.

The old man looked at the photo of Luna on his mobile phone screen and said, “Everyone can agree on a kitten.”

I asked him what he’d like to order.

“How about an omelette and bacon,” he said. “And tell Ned to make it to go. I don’t like leaving Luna for long.”

Before you go

This journal continues because a few readers quietly support it. If these pages matter to you, a small one-time gift below helps keep the work going.

Thank you for reading.

Subscribe to Weiss Journal.