Before the Doors Close for Good

That we remember who we are

One of the quiet gifts of travel is not what you plan to see, but what you stumble upon when you are unhurried and slightly lost.

That was the case years ago in New Orleans, a city held between river and lake, memory and music. My wife and I had arrived for a few days of wandering. Jazz floated from doorways. Beads clung to balconies, remnants of forgotten celebrations. There’s an old presence about the city, its ghosts and their stories hovering beyond sight but felt nonetheless.

On the afternoon of our arrival my wife wasn’t feeling well, so I set out alone. I found a coffee shop, ordered a latte, and sketched quietly in a Moleskine notebook. There is something grounding about the scratch of pen on paper in an unfamiliar place. It slows you down. It reminds you that you are a body, not a browser.

Walking back toward our hotel, I noticed a pair of large wooden doors on Orleans Avenue. Locked. Dark. Above them, a simple sign: Arcadian Books and Art Prints. I could not tell whether the shop was closed for the day or closed forever, but I filed it away the way one does with promising thoughts.

That evening, my wife felt better. After dinner we wandered beneath the galleries and trees, the air cooling, the streets loosening their grip on the day. When we turned onto Orleans Avenue again, the doors were open.

Warm light spilled onto the sidewalk.

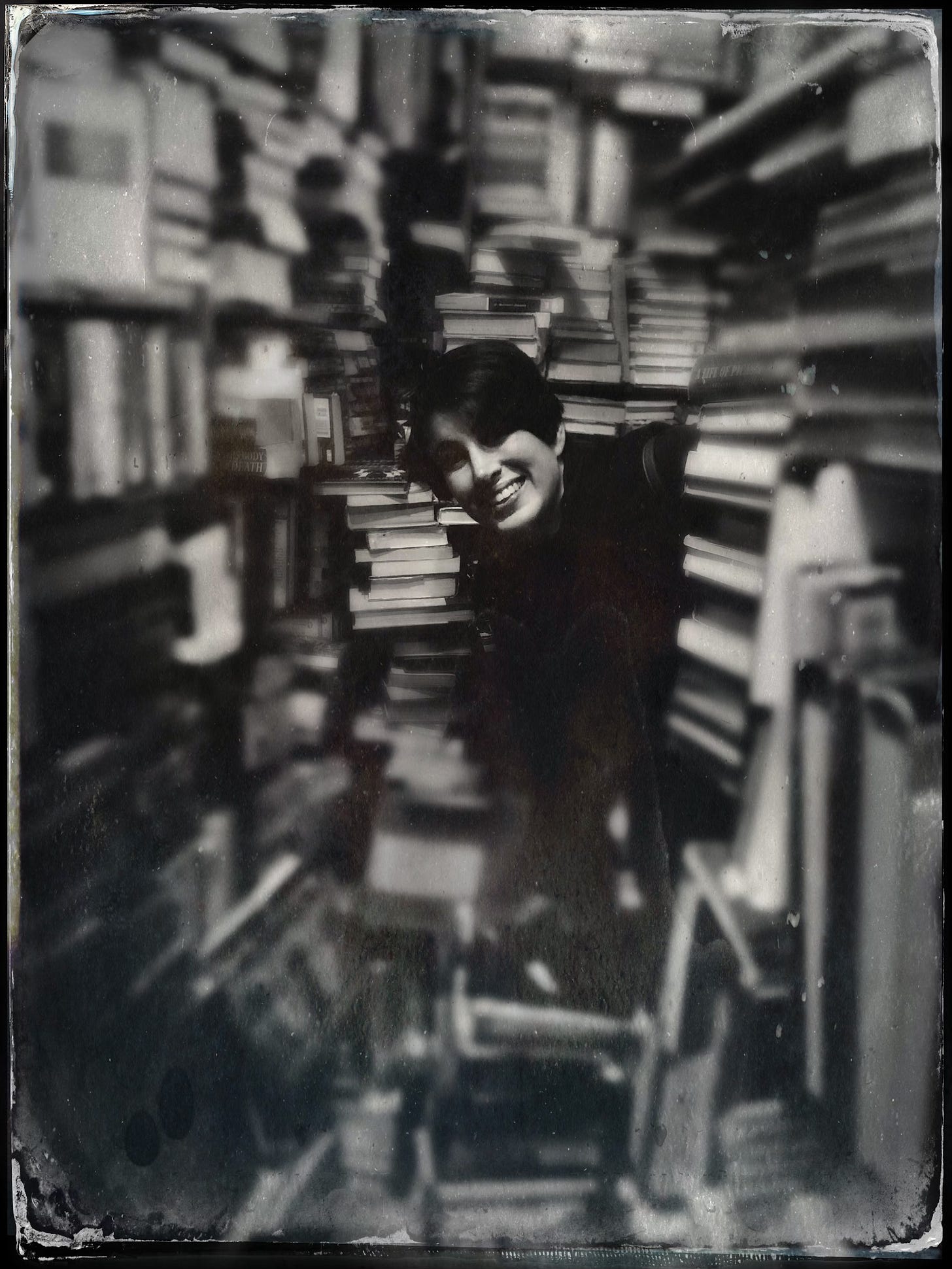

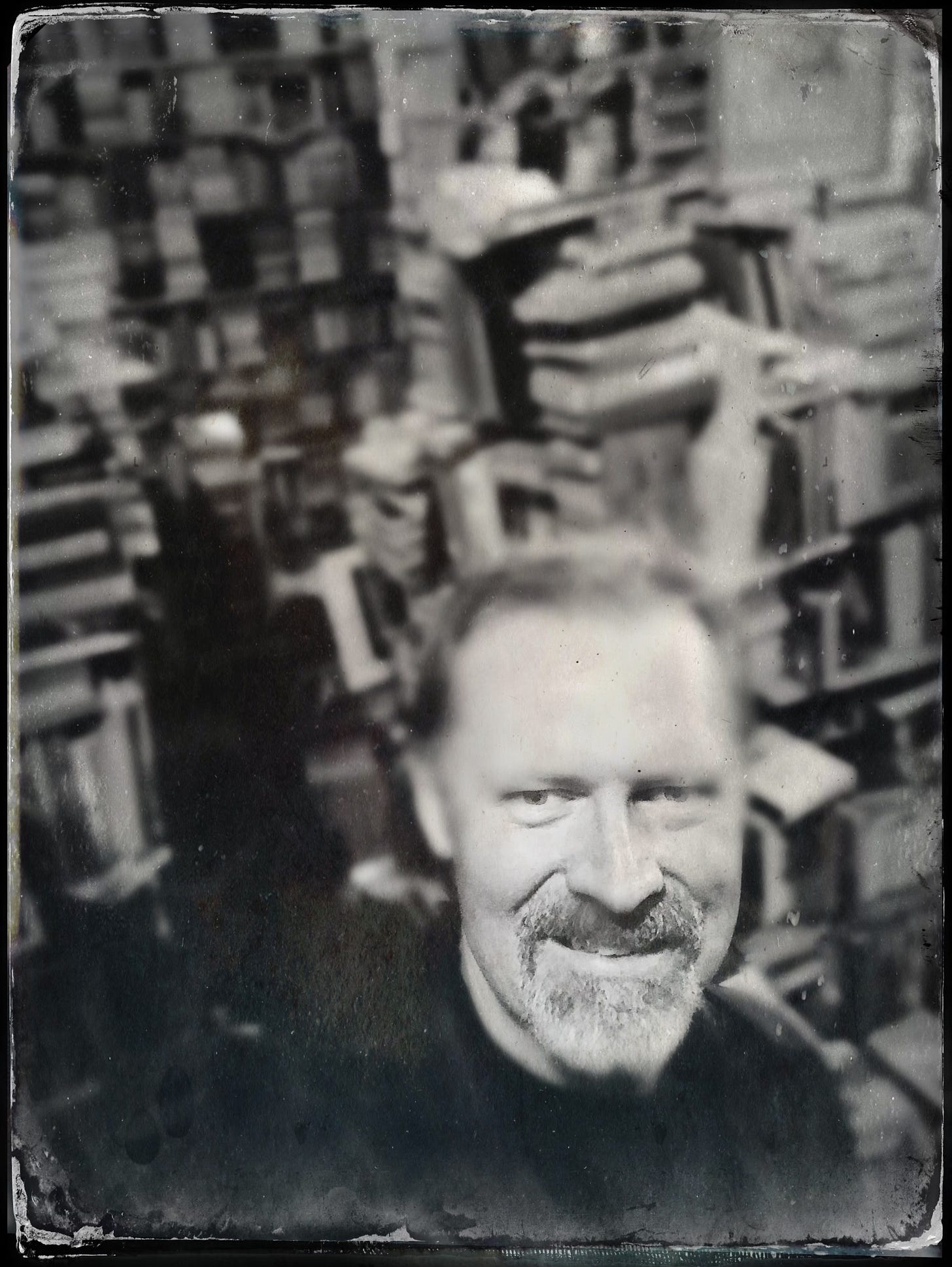

The proprietor stood outside, and without a word, we stepped in. Crossing the threshold of that bookshop felt like crossing time. Every inch of the interior was filled with books, stacked, leaning, bowing under their own weight. There was no clear order, only a kind of elegant chaos. Narrow passageways wound between towers of forgotten words. Dust hung in the air. The smell of paper, age, and neglect was unmistakable.

This was not a place designed for efficiency. It demanded patience. Attention. A slow hand.

As more people entered, the space tightened. Books shifted. Somewhere behind us a soft thud, another volume giving up its place on a high shelf, surrendering to gravity after years of being ignored. Some fell cleanly. Others landed awkwardly, spines twisted, pages flared open as if in protest.

I remember feeling an unexpected pang of sorrow for them.

In an age of glowing screens and endless feeds, books have become almost archaeological. Analog containers from a slower civilization. They ask something of us that modern technology does not: time, silence, sustained attention. They cannot be skimmed without consequence.

And yet, here they were, waiting.

An electric fan had been wedged improbably between two book arches, defying logic. Prints lay stacked against the walls. Black and white photographs stared back from another century. It felt less like a shop and more like a sanctuary for ideas that refused to disappear.

Old bookshops know things.

They know about grief, because they house the words of those who have lost children, spouses, entire worlds, and lived to write about it. Somewhere on those shelves was a battered copy of Joan Didion, holding vigil.

They know about guilt. Dante waits patiently. Dostoevsky, too.

They know about love, its longing, its ruin, its endurance. Austen. The Brontës. Poets who understood that the heart has always been a difficult instrument to play.

They know about childhood, and the ache of remembering who you once were. A worn copy of Charlotte’s Web can undo a grown man if he’s not careful.

And they know something else, something harder to articulate.

They know that wisdom is not optimized.

These days we are told by algorithms, by platforms, by the architecture of our devices that faster is better. Shorter. Louder. More visual. We are encouraged to watch rather than read, to scroll rather than sit, to consume rather than contemplate.

The historian Yuval Noah Harari has warned that we are no longer merely dealing with artificial intelligence, but with something closer to alien intelligence. Systems that do not share our biology, our slowness, our need for meaning, but nonetheless shape what we see, what we believe, and eventually who we become.

Information can now be generated, altered, personalized, and erased at a scale the human mind was never designed to navigate. Reality itself begins to feel provisional.

Books resist this.

A printed page does not update itself overnight. It cannot quietly change its mind. Its errors and insights remain fixed, accountable. A book is a moral object in this way. It stands behind what it says.

I thought of my father.

He used to tell me about evenings gathered around the radio, listening to voices conjure entire worlds. No screens. No images. Only imagination. When I was young, I dismissed this as nostalgia. Memories of a dinosaur.

Now I understand.

I have my father’s books. Sometimes I open them and find his handwriting in the margins, notes, underlines, small disagreements with the author. Long after his death, those markings feel like messages slipped forward through time. Proof that he was here. That he thought. That he wrestled with ideas the way we all must.

You can’t take a fountain pen to a screen.

Standing in that old bookshop, surrounded by dust and stories and quiet endurance, I felt the same connection. Human thought, suspended. Waiting for another human to meet it halfway.

We are organic beings.

We think best with our hands involved, turning pages, loading film, filling notebooks with ink. Cameras that force us to wait. Pens that slow our sentences. Journals that do not autocomplete our thoughts.

There is something almost divine about that friction.

Technology will continue to advance. It always has. But the human condition remains stubbornly the same. We still ache for meaning. For beauty. For truth that has been lived, not synthesized.

Old bookshops know this.

They stand quietly, holding the accumulated testimony of centuries, asking only that we enter without rushing. That we listen.

That we remember who we are before the doors close for good.

Before you go

This journal continues because a few readers quietly support it. If these pages matter to you, a small one-time gift below helps keep the work going.

Thank you for reading.

Subscribe to Weiss Journal.

This is truly some of your most beautiful writing. I read phrases over and over, the entire piece several times, and then once more aloud to myself. Deep, true, thoughtful, wise and philosophical. I treasure it. Thank you.

An ode to the bibliophiles, an ode to humanity, and a chilling reminder of what we are losing to AI.